When the Future Looked Brave and New

By JAMES CAMPBELL

Published: December 2, 2007

Aldous Huxley began his literary career on the edge of Bloomsbury and

ended it in Beverly Hills, the prophet of a dystopian future and advocate

of LSD. Huxley was so preoccupied by the dangers threatening civilization

that he could not rouse himself to defend it. The reader of this engrossing

collection of letters, many previously unpublished, is dismayed to find

him refusing to sign a declaration against Hitler — never mind fight — a

few weeks after the outbreak of war, because “I do not feel that

politics ... are my affair,” except “such politics as are

dictated by the need to ‘make the world safe for mystical experience.’ ” Support

from Bloomsbury old boys was not lacking: “Have you yet read [Bertrand]

Russell’s new book, ‘Which Way to Peace’?” he

asked a correspondent in 1936, as the Nazis prepared to trample over Europe. “It

is a most admirably lucid argument leading by remorseless logic to the

complete pacifist position.”

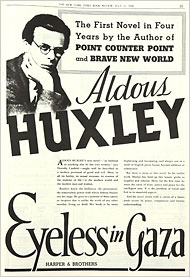

An advertisement from the Book Review, 1936.

ALDOUS HUXLEY

Selected Letters.

Edited by James Sexton.

497 pp. Ivan R. Dee. $35.

In his capacity as both letter writer and novelist, Huxley was most comfortable when communicating ideas about how to save the world, or to save Aldous Huxley, no matter how eccentric. By the time the war was over, he was dabbling in Scientology and giving credence to rumors of Martians in the skies above California. The reason scientists were not receiving their signals was simple, he told his son Matthew: “They are not using radar, but electro-gravitational waves, which will not be picked up until the suitable instrument exists.” Two “remarkable men” from Caltech were working on the problem.

Huxley, who died on the day John F. Kennedy was assassinated, was the model of the 1930s polymathic writer. Like his mentor D. H. Lawrence, he turned his hand to poetry, drama, travel and all manner of scientific and philosophical essays, in addition to fiction. He was, however, Lawrence’s opposite in practically every other respect, his pen being guided principally by the head rather than emotional or visceral instinct. The editor of “Selected Letters,” James Sexton, cites a memoir by the writer G. B. Stern, who met Huxley on a few occasions. If anyone raised a topic “with any personal implication,” Stern wrote, Huxley cut them off. “Provided a subject could be kept impersonal, however, he went into it with mathematical accuracy.” To Naomi Mitchison in 1938, he outlined a work in progress:

“A kind of novel which attempts not only to describe human antics, but also to explain them in terms of a general theory of antics which tells a kind of story and at the same time tries to analyze the assumptions we make every time a story is told; which builds with verbal and anecdotal bricks that are taken to pieces in the process of being laid.”

By this time, Huxley was resident in Hollywood, working on projects ranging from a treatment of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” for Walt Disney to “a musical-comedy version of ‘Brave New World.’ ” Neither was made, though several other Huxley scripts reached the screen. The most famous outing for his intellectual promiscuity was his experimentation with LSD, which, combined with pioneering small-is-beautiful beliefs, brought a revival of interest in Huxley’s work in the 1960s. His best-known book after “Brave New World” is “The Doors of Perception,” which, as Sexton puts it, suggested “the name of the rock band the Doors.”

The main pleasures of “Selected Letters” are to be found in the social sphere and derive largely from correspondences with two women: Lady Ottoline Morrell, the Bloomsbury hostess who ran a busy country estate at Garsington, Oxfordshire, and Mary Hutchinson, a member of the circle and lover to both Aldous and his wife, Maria, despite being herself married with children. The letters to Ottoline Morrell are those of an apprentice to a grande dame. Huxley first visited Garsington Manor in 1915, meeting there and thereabouts Russell, Lawrence, Clive Bell, the art critic Roger Fry and the painter Duncan Grant, among others. A graduate of Eton and Balliol, he was made welcome until the publication of his first novel, “Crome Yellow” (1921), which seemed to Lady Ottoline to satirize her hospitality. “Your letter bewildered me,” Huxley protested. “For, after all, the characters are nothing but marionettes with voices, designed to express ideas and the parody of ideas. A caricature of myself in extreme youth is the only approach to a real person.” He conceded that it had been a mistake “to use some of Garsington’s architectural details.”

A rereading of “Crome Yellow,” which depicts a group of dilletantes playing country-house games while the fog of war still lingers, suggests that Lady Ottoline had grounds for complaint. Huxley could console himself with the knowledge that he had departed Garsington with profitable subject matter — “I have been so busy being famous that it has been impossible to write to you,” he told Mary Hutchinson from New York in 1926 — and a wife and a mistress. Hutchinson, who was also a lifelong friend of T. S. Eliot, lacked the creative drive of many of her friends, making up for it in sexual invention. “Why don’t you come to us here, Mary?” Huxley wrote from Italy in 1926, extending the invitation on behalf of Maria and himself. “We could renew all the pleasures — invent new ones perhaps, if there are any that we have still left untried.” On Nov. 12, he thanked her for her postcard “of the androgyne”; two days later, another card arrived, with Bronzino’s Venus on one side “and you emerging from the written words as deliciously naked and desirable, on the other.” On St. Valentine’s Day, the following year, he sent a sonnet in praise of Mary’s “hermaphroditic arts,” welcoming Cupid’s arrow that directs pain “down sweet torturing roads, / Till pleasure dazzling explodes.”

The triangular affair cooled into friendship, while the Huxleys circled the globe. “What a monstrous thing it is to have no money of one’s own,” Aldous complained to Naomi Mitchison from an unnamed “extremely beautiful” location in Italy. Lack of funds proved no obstacle to a six-month tour of the Far East, followed by a return to Tuscany. Eventually, Huxley, who found the architecture of Florence “just boring, like the Oxford Colleges,” settled in Los Angeles, working for the dream industry while continuing to depict the nightmare to come.

The editing of the letters is wayward, when not simply baffling. One after another, projects and personages appear on the page, unannotated, unexplained. “I am enclosing a rather rambling disquisition ... which you might care to print in the Criterion,” he wrote to Eliot in 1924. What the disquisition was, or if the journal published it, we are not told. “I was charmed by your article,” he told Hutchinson the previous year — which article we are left to guess. Some correspondents are in receipt of several letters before being introduced, if introduced at all. One example will have to suffice. Huxley wrote to Catherine Carswell in 1932 that he had had difficulty obtaining her book, and signed off with regards “to your husband.” Which book? What husband? There may be readers unfamiliar with Catherine Carswell, so here goes: she was a Scottish novelist of the Edwardian period and a close friend of D. H. Lawrence. The (very good) book referred to is “The Savage Pilgrimage,” about their relationship, written in response to an earlier memoir by John Middleton Murry. Her husband, Donald Carswell, was a journalist and the author of a popular study of Walter Scott. Not so difficult, after all.

James Campbell’s books include a biography of James Baldwin and

a forthcoming collection of essays, “Syncopations: Beats, New Yorkers

and Writers in the Dark.”